By Sarah Bostick

Every five years, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service conducts a census. The 2017 Census of Agriculture captured in numbers what we see happening all around us: Farming is changing.

GREENER GROWERS

One of the most notable changes is that a growing number of farms in America are run by new and beginner producers — those who have operated a farm for fewer than 10 years.

As of 2017, more than a quarter of all producers in America had farmed for 10 years or less. In 2017, there were 908,274 new and beginning farmers producing on over 193 million acres of land. In Georgia, Florida and Alabama, the percentage of beginning farmers is even higher than the national average: 33, 31 and 30 percent, respectively.

This growing demographic of new farmers is also younger than the average farmer in America: 46.3 years old compared to 57.5 years old. Nationwide, 26 percent of beginning farmers are under the age of 35 compared to only 8 percent of all U.S. farmers.

New farmers are much more likely to operate a small acreage farm. Beginning farmers are also significantly more likely than the average American farmer to work off-farm, earn the majority of household income from off-farm jobs, have a higher debt-to-asset ratio and have a higher expense-to-sales ratio.

Another reality is that beginning farmers are more likely to be first-generation farmers. For as long as humans have farmed, knowledge and land have been passed down from one generation of a family to another. That time-honored tradition is changing.

The National Young Farmers Coalition (NYFC) is a non-profit organization with a mission of supporting young beginning farmers. In 2017, with the help of 94 partner organizations, NYFC surveyed 4,746 farmers across the nation. The survey (see www.youngfarmers.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/NYFC-Report-2017.pdf) showed that 75 percent of the respondents under the age of 40 did not grow up on a farm.

So how is the next generation of farmers learning to farm?

There are countless ways that organizations and individuals are creatively helping new farmers learn. Some of those ways are through incubator farms, farmer training programs, farm apprenticeships, conferences, farmer-to-farmer networks, and college and university student farms.

INTERNING AND VOLUNTEERING

In 2016, I was managing the University of Florida’s Field and Fork Farm and Garden program. The program provides an accessible place for students to get their hands dirty and learn to grow food. The program offered a dozen internships each semester, with many more applications than positions. A bright-eyed sophomore named Ida Vandamme applied that fall.

I still remember Vandamme’s interview. She met us in the carrot field and we showed her how to weed. Without hesitating, she started the delicate work of hand weeding a 150-foot bed. While working together, we asked her formal interview questions. She didn’t skip a beat. She was clearly a natural at thinking, talking and doing at the same time — a skill that is essential in farming.

Most students, including Vandamme, did not get an internship that year. We encouraged them all to volunteer that semester and apply next year. Vandamme took that advice to heart. She became one of the most consistent volunteers, happily harvesting cucumbers and stringing tomatoes while asking an endless stream of questions. She wanted to know how the things she was learning in plant science and sustainable food production classes related to what she was experiencing on the farm. Vandamme got the internship the next year and worked with Field and Fork until graduating in 2018.

TRANSFER OF KNOWLEDGE

One of the first farmers I met when I started my job as the sustainable agriculture Extension Agent in Sarasota County was Tiffany Bailey, a fifth-generation farmer and owner of both Bayside Sod Farm and Honeyside Farm, which produces vegetables. She grew up operating tractors, fixing machinery and understanding how to manage an agricultural business. In my first conversation with Bailey, she told me that she feels privileged that she grew up knowing how to farm and had a family farm to take over when her dad retired. She realized that most young people who want to farm start from scratch and she wanted to find a way to help change that for someone.

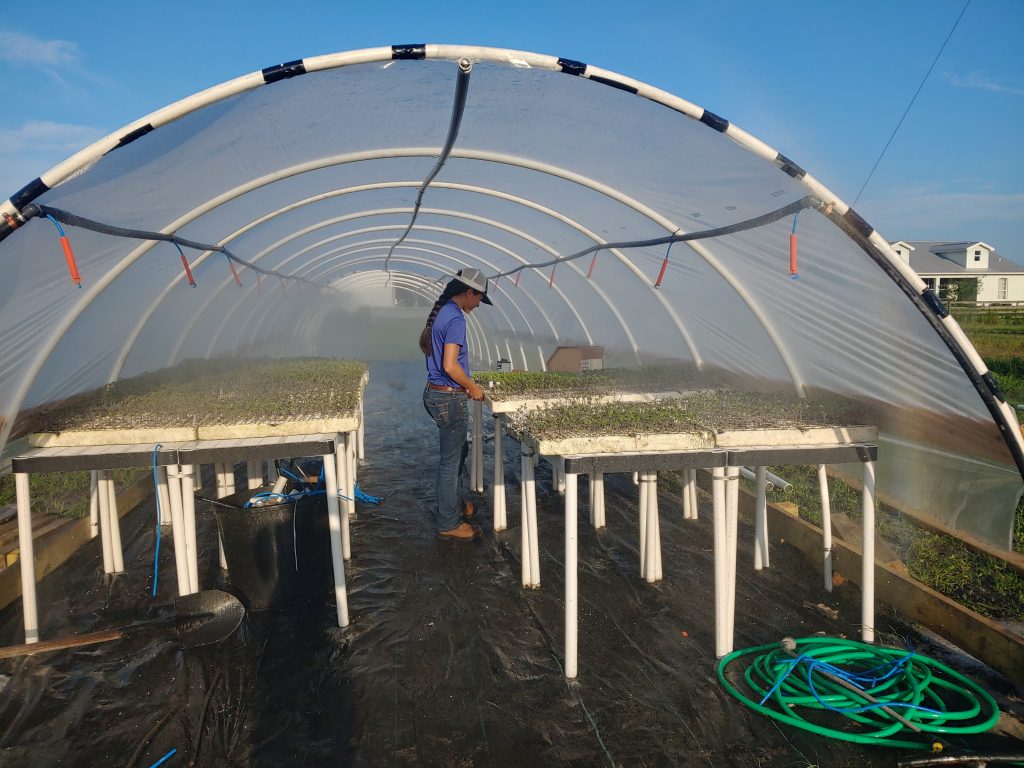

A few months later, Bailey decided that it was time to train someone else to run Honeyside. She wanted Honeyside to grow and knew that she didn’t have enough time to do it herself. She decided to hire a farm manager. One of the people who applied for the job was Vandamme.

When asked how qualified she was for the farm manager job that she has now held for a year and a half, Vandamme bursts into laughter and says, “Not at all!” Bailey knew that Vandamme wasn’t an experienced farmer. But she didn’t see this as a bad thing; she saw it as an opportunity.

Bailey said she decided to take a chance on hiring Vandamme to manage her farm because “It is important to think about the responsibility that you have as an agriculture leader. You get to positively impact someone’s life. It doesn’t always work great. You have good days and bad days. But at the end of the day, the thanks you get from the people you have empowered to learn to grow food is amazing.”

Hiring Vandamme forced Bailey to get all the details out of her head and create systems that other people could easily plug into. “If only you know how to do everything, you can’t grow and you can’t further your impact,” says Bailey. “You are going to stay where you are.”

Bailey has some advice for established farmers who want to be part of training the next generation of farmers: The transfer of technical knowledge has to be hands-on. “Keep it teachable and keep it repeatable,” she advises. What doesn’t work is thinking that everyone is going to be good at doing everything from the get-go — that take times.

Vandamme has some advice, too: Aspiring farmers can’t be scared to take the leap when an opportunity presents itself. For Vandamme, applying for a job managing a 10-acre vegetable farm was her big leap.

“Coming to Honeyside is the best thing that has ever happened to me,” says Vandamme. “I think I won the lottery with Tiffany.”

For Vandamme, a young first-generation farmer, the hardest thing to learn about managing a farm has been putting all the little pieces together into the big picture. Bailey is committed to helping her with this process.

Vandamme dreams of owning her own farm someday. Land access is the No. 1 barrier to farming for young farmers, and Vandamme is no exception. Bailey hopes that Vandamme stays with Honeyside for a long time. But she knows that Vandamme will probably move on someday — either to start her own farm or work on a larger farm. Bailey hopes that by the time Vandamme moves on, she will leave with the skills she needs to succeed as the next generation of farmers.

Farming in America is changing. Farming was once something that the younger generation learned from their parents, just as land was passed down through the generations. As more and more farm kids grow up and leave the farm, that generational knowledge is being lost. But it doesn’t have to be lost, and you can be a part of making sure that deep agricultural knowledge is passed on. I encourage new and established farmers to reach out to one another in the great American tradition of cultivating the next generation of farmers.